Getting It Right

I had planned to stop at Fort Donelson only long enough to drop off a copy of Beyond All Price, whose cover features a photograph taken on the grounds of that Civil War battle site. The young woman at the desk was already flustered, and, when I asked for the park ranger, she threw up her hands, saying “You, too?” and went scurrying out of the building, presumably in search of that missing gentleman.

An African-American couple wandered aimlessly around the small room, shaking their heads in amusement at the sudden departure of the young clerk. We smiled and exchanged the usual pleasantries, since there seemed to be no hope of the imminent arrival of someone in charge. The gentleman asked about the book I was clutching, and I launched into my elevator speech about the story of a Union nurse in Civil War South Carolina. To my surprise, he nodded, saying, “Oh, yes, I know the place well. My grandfather was there.” We were now chatting like long-lost family.

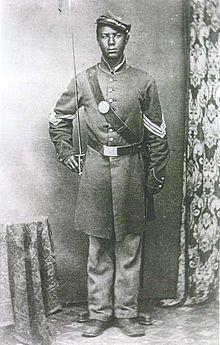

The man’s grandfather, a member of the 55th Massachusetts, had recently been awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his role in the Battle of Honey Hill. He showed us a picture frame containing the image of the Medal of Honor and an old photo of a black soldier. “I try to deliver one of these to every place where my grandfather fought,” he explained. “He wasn’t a soldier at the Battle of Fort Donelson because black men weren’t yet allowed to enlist, but he was here, acting as a horse servant to Major John Warner of the 41st Illinois Volunteers.”

Intrigued by the encounter, I did some research. Andrew Jackson Smith was a slave who ran away from his Kentucky owner, Elijah Smith, who intended to take him to join the Confederate Army in 1861. Andrew fled to the free state of Illinois. Because blacks were not eligible for military service, he signed on as Major John Warner’s horse servant in the Battle of Fort Donelson.

At the Hornet’s Nest at Shiloh, Andrew was hit by a rifle bullet that lodged just under the skin of his forehead. While recuperating in Illinois, he learned of the Emancipation Proclamation and immediately renewed his desire to join the Union Army. He volunteered for the famous 54th Massachusetts, the black regiment whose story was told in the movie “Glory.” He arrived after their roster was full and so had to settle for their sister unit, the 55th Massachusetts.

The 54th and 55th Massachusetts fought side by side throughout the war. In November 1864 they were sent to clear the way for Sherman’s March to the Sea by cutting the Charleston and Savannah Railroad near Grahamville, SC. A force of some 5000 men started up the Broad River from Hilton Head, but dense fog and poor maps led to several units running aground. Marching troops fared little better, becoming hopelessly lost and bogged down in the swamps.

The Massachusetts regiments finally encountered Confederate fortifications across the road to Pocotaligo and fought a hopeless battle. When their color bearer was killed by a mortar shell, Corporal Smith grabbed the flag from his dying hands and carried it through the rest of the battle, even though it made him a prime target and exposed him to extraordinary danger

For his bravery, many felt that Smith should have been awarded a medal on the spot, but due to the enormous casualties suffered by staff officers, the paperwork was never completed. Smith received only a promotion to Color Sergeant after the battle.

In 1916, he was formally nominated for the Medal of Honor but was turned down because of the lack of official records. Smith died in 1932, his bravery still unrecognized.

Andrew S. Bowman, the humble man I met at Fort Donelson, raised the issue again after he had helped his own son research their family ancestry. A new appeal resulted in the awarding of the Medal of Honor to Andrew Jackson Smith. The ceremony took place in President Bill Clinton’s Oval Office on January 16, 1991.

At the end of the ceremony, the President turned to Smith’s family:

“It’s taken America 137 years to honor his heroism. We are immensely honored to have with us today eight of his family members, including Andrew Bowman, here to receive the Medal of Honor on behalf of his grandfather, and Mrs. Caruth Smith Washington, Andrew Jackson Smith’s daughter, and a very young 93. I want to say to all the members of the Smith family, sometimes it takes this country a while, but we nearly always get it right in the end. I am proud that we finally got the facts and that, for you and your brave forebear, we’re finally making things right.”