The Healing Power of Writing

As I toured the country last year to do readings from my book, Gated Grief, often, someone in the audience asked me, “How long did it take you to write the book?” That seemingly straightforward question has no straightforward answer. The origins of Gated Grief, a portrait of my father's PTSD from World War II and how it shaped my childhood, lay in my fervent erratic outpourings in the journal I began “keeping” in high school. (strange word: keeping) Some of those entries became a part of the book.

I kept up the journal writing for the next thirty years, figuring someday it might direct me to the subject of a memoir I knew I wanted to write. But as the memoirist Vivian Gornick emphasized in a workshop I took, “A memoir isn't an exercise in excavating. It needs to be about something.” I had no idea what my story was about other than depression and abandonment. To flush out the story, I needed to understand what caused the depression, what led to the abandonment, and who abandoned whom in my family. But I existed in a fog, my senses unable to provide me the essential information. My writing seemed a futile exercise of describing the loop I was stuck in, as page after page fixated on the same scene—the one where I was separated from my mother in a police station.

It wasn't until I was teaching a literature of the Holocaust course that a break in the loop opened. My class read memoirs by survivors of the Nazi concentration camps and by the children of survivors. We learned how the traumatized parent unwittingly passes along their trauma to their children, many of whom wrote, “It's as though I was a prisoner at Auschwitz.” When I assigned oral histories of GI liberators, I thought my motivation was to provide the students an American perspective on the Holocaust and how the Holocaust became a part of American history through the witnessing of the GIs. After reading words such as “My mind somersaulted and froze” and “If it wasn't for the photographs I took, I wouldn't believe I ever was there,” my students asked me, “Did the trauma of the liberators affect their children like the trauma of the survivors affected theirs?”

I grasped the desk next to me as my knees buckled.

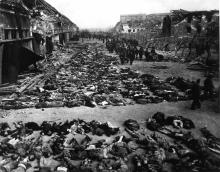

This question had personal significance for me. Twelve years before, days after my father passed away, I found in his medical office a box of photographs he had taken in Europe as an army doctor in World War II. At the bottom of the box lay images of blurred stripes, skeletal bodies. His handwriting noted on the backs, “Nordhausen Concentration Camp, April 12, 1945.”

My father had mentioned landing on Utah Beach right behind the troops on D-Day, being at the Battle of the Bulge. He had never mentioned Nordhausen, not even to my stepmother, his wife of twenty-two years.

When my students asked me the question in 2003, I could not find any books that explored the psychological and emotional consequences for the Allied forces that liberated the Nazi concentration camps. In fact, no book existed that discussed the trauma of the Allied troops from the war, as if , because the war was a just war, the combatants did not suffer trauma.

So I set off to meet GI liberators and ask them questions no one had ever asked them.

“What was your experience when you entered the camp?”

“How did witnessing the camp change you?”

“Have you ever talked to your spouse, your children about your experience?”

Like my father, none of them had spoken of it to their children. Like me, their children grew up in a vault of silence and the depression that follows silence.

I began to connect the dots, to understand what my story was about.

Every veteran I spoke with time traveled as soon as they began remembering Dachau, Buchenwald, Nordhausen, Mauthausen. As they got to the point in their narrative where they walked through the gates of the camp, they froze in mid-sentence, their mouths open, words unable to come forth. Tears flowing, most then left the room.

I knew this time warp. Until I began my journal writing, whenever I thought of the day my mother was arrested, my mind would freeze, my body shake. And I realized that my journal writing—that endless seemingly obsessive writing/rewriting/rewriting—had altered my relationship to the traumatic moment. The writing defused its terror, its power over me, by exposing it to the light of day where it gradually shriveled. My journal writing had been healing me and led me to a place where I could tell my story, do the necessary research, be present for these veterans and help them begin processing the most pivotal moment in their life.

The most satisfying consequence of my meeting these veterans and speaking with them is that two have now written memoirs, and another four have begun speaking publicly about being witnesses to the Holocaust. They want to add their testimony to the historical record.

Psychologists call the effect of writing about trauma “exposure.” Some psychologists have made writing's power to heal the subject of their professional research. But we writers have known this for centuries, though we may have not put words to it or documented it with empirical data. Now we can put our invaluable experience to the service of our newest generation of veterans. Let us help them find the words for their experiences, so that rather than trying to lock it away with silence, they will give voice to their pain and grief. And then not only will they begin to heal, but the rest of us can begin to understand and stand in community with them.

Leila Levinson is the author of Gated Grief: The Daughter of a GI Concentration Camp Liberator Discovers a Legacy of Trauma, which won the MWSA President's Award in 2011. Leila will be doing an ebook launch of Gated Grief on Amazon from February 16-23. It will be available that week for $1.99.