The nonfiction behind the war fiction

A friend told me I was being too “journalistic” when answering interview questions about

A friend told me I was being too “journalistic” when answering interview questions about

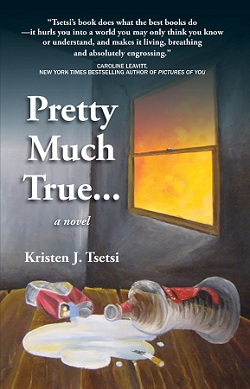

Pretty Much True… .

You wrote a fictional story in which the characters and actions were different but the feelings and the fear were the same. Get PERSONAL.

I never wanted to do that before, because I wanted to emphasize that the overall feeling of the experience, not my experience but the experience, was what was important. But she made me see that one experience, the story, wouldn’t exist without the other, the reality.

Most of the short stories I’ve written had something to do with my life at the time, something Joseph Dilworth of Pop Culture Zoo touched on in his review of my short fiction collection Carol’s Aquarium:

I have no doubt that each one of these stories is drawn from a moment in time from the life of Kristen Tsetsi, whether they are shockingly true or re-purposed for a fictional event.

Those stories are, as he said, illustrations of real life. A marriage I wasn’t happy in. Insecurity about something or other. Anger toward someone. Unrequited love. Fear of dying. A toy fish that, when wet, turns into a woman.

The truth is, none of my stories have been nonfiction, but all were ultimately true. I wrote them because I knew I wasn’t the only one having those feelings, and I wanted – because I enjoy writing – to write about things I knew others might find guilty relief in relating to.

Pretty Much True… was different from my short fiction because I didn’t start it until about a year after Ian was home safe. Why write it if the angst had passed? Was it a catharsis? Was it an attempt to try to offer support to others? (No to both.)

After Ian came home, we’d watch war movies now and then (I refused to watch anything war-y while he was gone, because people DIE in war movies, for God’s sake). At the end of each movie, more often than not, the service member goes home to a smiling blonde with happy breasts who’s jumping up and down in a sundress, ready for a hug.

I used to think that was the extent of it: man leaves for war, woman misses man, man has many harrowing, life-changing, unforgettable experiences he can never talk about because they’re too complex, man comes home, woman gives hugs, says, “I missed you,” and throws a party.

That was until I’d experienced it myself, when I learned that it’s equally hard to talk about what happens while waiting because it, too, is complex. I learned what homecoming day means – that is, that it isn’t a simple, happy hug, that there’s something behind her hug and smile just as there’s something behind his.

That was the story that had yet to have more than one or two people dig into it and explain it in a way that didn’t pretty it up. There’s a temptation, I think, to pretty it up like that because no one wants to say, “It can be as bad at home as it is over there.”

*Gasp!* How dare–!

The thing of it, though, is that it’s not a competition. It’s not about who had or has it “harder.” All war stories are unique, and all war stories are valid and valuable.

And much of war is psychological (I’ve heard it said). Much of it is waiting, and service members will tell you that, themselves. Ian wrote a letter from where he’d been waiting for two weeks for things to start in Iraq early 2003, and in the letter (we had no email until a few months in), he told me that as much as he didn’t want to get involved in any kind of combat, the waiting was almost worse. It was time to get on with things one way or the other.

At home, the wait is constant. There’s no “getting on with things” until the day it’s over. Consider this: Many soldiers know from one day to the next what their plans are. One day, they might be hanging out at the FOB (forward operating base) watching DVDs on a laptop or playing cards, the only danger an attack of heat or scary spiderbugs.

That same day, as he plays cards, the person who loves him could – at that same moment – be staring at his pictures, crying, wondering if someone is going to call at that second to tell her he’s dead.

There’s no break, you see. It’s always a case of not knowing. And it’s an utter mind-f***, to put it delicately.

I wrote Pretty Much True…–most of whose scenes, even when the strictest fiction, were created around a memory of a particular day or week or feeling—to explain the inexplicable, to be able hand it to someone and say, “Well, it’s like this…”